‘Don’t Look Back In Anger’: Counting the Cost of Lebanese Nostalgia

By Maria El Sammak

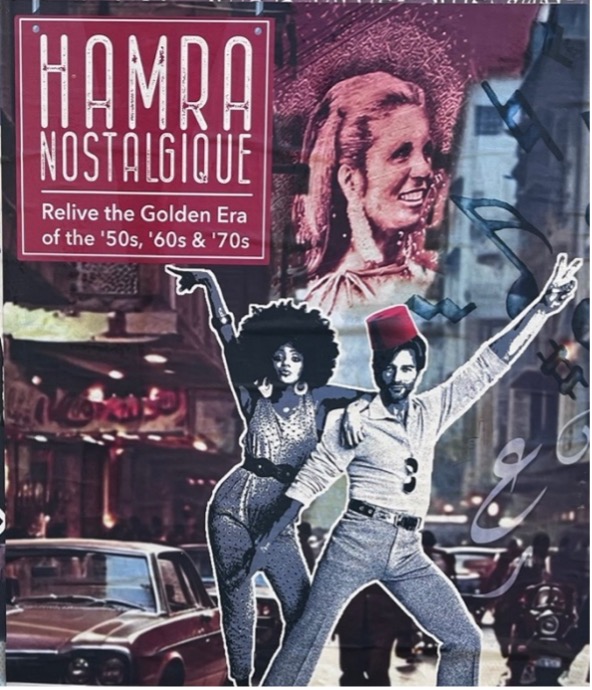

While walking through the streets of Hamra, Beirut, in autumn this year, I came across an advertisement for a restaurant. The poster promised that customers would be able to ‘taste the Golden Age of Beirut.’ A few metres later, another advertisement appeared: this time it was for an event inviting participants to ‘relive the Golden Era of the ‘50s, ‘60s & ‘70s Lebanon.’

Such references are not unusual. Beirut’s streets are saturated with nostalgic evocations of its once-prosperous past. In May 2025, ahead of the Municipal Elections, Downtown Beirut was littered with billboards bearing political messages. Against an image of 1950s Martyrs’ Square, an electoral coalition under the name of Beirut Loves You promised its constituencies that ‘the glory days will return.’ Another billboard from the same campaign floated the identical line over a photo of a bustling Place de L’Etoile, this time taken in the early 2000s during the city centre’s post-war reconstruction – a project which itself drew heavily on nostalgia for Lebanon’s ‘Golden Age’. The campaign’s message was clear: Lebanon’s so-called glory days of the 1950s and 1960s can be recaptured, resuscitated, and projected onto the Lebanon of today. Within this interplay between memory and imagining, nostalgia becomes more than mere sentiment – it becomes a political tool.

An advertisement in central Beirut. Credit: Maria El Sammak

Nostalgia is a complex emotion that describes a desire to recapture or revive aspects of the past, shaping the way people imagine their future. Although not inherently political, nostalgia has been progressively politicised, fuelling the rise of ethnic nationalism and the populist radical right in Europe and the United States, as it offers a ‘return’ to a secure, idealised past in the face of uncertainty and perceived threats from an increasingly globalised world.[i] In Lebanon, people may look back at the ‘Golden Age’ as a time of (relative) stability and prosperity – but allowing oneself to be continually swayed by this romanticised version of the past weakens the ability to respond to the demands of the present and the challenges of the future.

A billboard in downtown Beirut stating that the ‘glory days will return’, against the background of a pre-war Martyrs’ Square – photo taken by author in May 2025. Credit: Maria El Sammak

Lebanon’s ‘Golden Age’: prosperity for the few?

Lebanon’s ‘Golden Age’ refers to the 1950s and 1960s, when the country underwent rapid economic and infrastructural development.[ii] With its flourishing banking sector and booming tourism industry, Beirut emerged as a regional cosmopolitan hub, and it was during this era that Lebanon gained prominence as the ‘Switzerland of the Middle East’ and its capital the ‘Paris of the Orient.’ These labels were further cemented after the 1956 Bank Secrecy Law that attracted foreign capital and transformed Beirut into a financial haven.

Yet, while banks’ profits soared, the wealth they generated failed to translate into broader social development. An economy increasingly dependent on finance, commerce, and luxury services left little space for industrialisation or agricultural reform. As a result, despite its cosmopolitan façade, Beirut came to embody stark socioeconomic inequality, its prosperity flourishing at the expense of its peripheries, deepening the rural-urban divide. A select few – traders, bankers, and members of the oligarchic elite – accumulated immense wealth, while many others were left behind.[iii]

Unsurprisingly, the frustrations and grievances caused by this inequality erupted into protest. In 1958, while the country was split over Lebanon’s pro-Western foreign policy, citizens took to the streets to demonstrate their growing resentment at the uneven development. The protests exposed the fragility and injustice of the elite-dominated economic model, and these tensions continued to escalate right up to the eve of the Lebanese civil war in 1975, when they exploded again.[iv]

Utilising nostalgia after the civil war

Despite the fact that socioeconomic inequality was one of the factors that contributed to the outbreak of civil war, decision-makers drew heavily on nostalgia for Lebanon’s ‘Golden Age’ to shape the post-war reconstruction of Beirut. When Rafic Hariri became Prime Minister in 1992, his vision of transforming Beirut into the ‘Singapore of the Middle East’ reflected a desire to restore the city’s pre-war regional and international standing.[v] Beirut’s Central District, once known for its cosmopolitan ‘Souk’ or ‘Bourj,’ became an exclusive retail centre hosting high-end brands that only a small segment of Lebanese society could afford. This space, which had previously welcomed people from all walks of life for business and social exchange, was transformed into an exclusive area which favoured the wealthy. The reconstruction may have aimed to revive the commercial spirit of the ‘glory days’, but it ultimately did so at the expense of reconciliation, further deepening divisions in the capital.

Alongside the physical reconstruction of Beirut, decision-makers also turned to the 1950s and 1960s to guide Lebanon’s post-war economic rehabilitation. In practice, this meant re-financialising Beirut through investments in luxury real estate, the banking sector, and transnational financial flows managed by the Central Bank. Other sectors, such as agriculture, manufacturing and public infrastructure, were pushed to the margins.[vi] This system, which again promoted the interests of a narrow elite over those of the rest of the population – and was characterised by a culture of corruption and impunity – ultimately led to the country’s economic collapse in 2019.

A billboard in downtown Beirut, titled ‘the glory days will return’, against a background of post-war downtown Beirut – photo taken by author in May 2025. Credit: Maria El Sammak

Lebanon following the financial crisis: Continuity, not reform

Today, six years after the 2019 financial crisis, Lebanon has once again failed to implement meaningful structural reforms to its economic model. Negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) over potential aid and loans, which began in 2022 but were postponed several times, have yet to yield any results. While the IMF continues to push for reforms, Lebanon’s political elites and the banking sector remain unwilling to accept any agreement that might threaten their interests.[vii]

Instead of confronting the flaws of a system that has repeatedly revealed its fragility, Lebanon’s ruling class has doubled down, further entrenching an economic model designed to self-destruct. In this light, calls for a return to the ‘Golden Age’ reflect more than a shared longing among decision-makers to recapture the prosperity of the 1950s and 1960s. They signal a determination to preserve the old order: one that safeguarded the affluence and privilege of the few at the expense of the many.

Why looking back won’t save Lebanon

In Lebanon, the so-called ‘Golden Age’ continues to cast a long nostalgic shadow. It appears in familial stories passed down by grandparents recalling the economic boom of the 1950s and 1960s, and in taxi drivers’ tales of foreign tourists who once crowded the Hotel District, skiing in the snow-capped mountains by morning and swimming in the Mediterranean by afternoon. But beneath this seemingly harmless recollection lies something more threatening: a romanticisation of inequality, impunity, and injustice.

A flyer advertised in central Beirut. Credit: Maria El Sammak

While idealised visions of the pre-war era may offer comfort to parts of the population in times of crisis, they also distract leaders from addressing present-day priorities. After the civil war, rather than pursuing meaningful state-building, decision-makers resurrected the economic model of the ‘Golden Age’ wholesale, without reckoning with its flaws or critically heeding the lessons of both 1958 and 1975.

This pattern persists today as Lebanon seeks to re-financialise its capital following the 2019 financial meltdown and the most recent war with Israel. Instead of delivering long-overdue reforms demanded by the international community, Beirut held a so-called ‘investor conference’ in November 2025, in an attempt to reinvigorate the Lebanese economy. Participants included Arab investment funds and prominent global firms, including BlackRock, Morgan Stanley, and General Atlantic.[viii] Lebanon once again turned to the economic model of the ‘Golden Age’ to rebuild its capital in the wake of crisis and conflict.

It is important to push back against the prevailing nostalgia for Lebanon’s so-called ‘glory days’ and instead expose the systems of violence and impunity that were already taking root at the time. It is only through a critical reflection of the past (both pre-war and post-war) that we can challenge the state’s capture by an entrenched ruling class and ultimately pursue an equitable reform agenda that holds the political, banking, and business elite accountable, without further burdening the Lebanese citizens, who have already borne the heaviest costs of the crisis.

Maria El Sammak is a Research Assistant on on the Cross-Border Conflict Evidence, Policy and Trends (XCEPT) research programme. She holds an MA in Conflict, Security and Development from King’s College London, and she previously worked with the Berghof Foundation in Beirut, focusing on peacebuilding and conflict transformation. Maria’s research explores questions of memory, violent conflict, and post-conflict dynamics in Lebanon.

[i] Gabrielle Elgenius and Jens Rydgren. “Nationalism and the Politics of Nostalgia.” Sociological Forum (Randolph, N.J.) 37, no. S1 (2022): 1230–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12836.

[ii] Sara Fregonese. “Between a Refuge and a Battleground: Beirut’s Discrepant Cosmopolitanisms.” Geographical Review 102, no. 3 (2012): 316–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1931-0846.2012.00154.x.

[iii] Fawwaz Traboulsi. A History of Modern Lebanon. 2nd Edition. London: Pluto Press, 2012. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt183p4f5.

[iv] Cobban, Helena. The Making Of Modern Lebanon. 1st ed. United Kingdom: Routledge, 2019. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429312465; Trabousli, A History of Modern Lebanon, 2012, 165-166.

[v] Guilain Denoeux and Robert Springborg. “Hariri’s Lebanon: Singapore of the Middle East or Sanaa of the Levant?” Middle East Policy 6, no. 2 (1998): 158-73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4967.1998.tb00317.x.

[vi] Julia Sakr-Tierney. “Real Estate, Banking and War: The Construction and Reconstructions of Beirut.” Cities 69 (2017): 73-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2017.06.003.

[vii] Philippe Hage Boutros, “Lebanon’s Unified Front for the IMF Falls Apart in Washington, ”L’Orient Today, October 20, 2025, https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1481884/lebanons-unified-front-for-the-imf-falls-apart-in-washington.html

[viii] “Economic Minister and Head of the Economic and Social Council Launch the ‘Beirut One’ Conference,” L’Orient Today, October 21, 2025. https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1482041/economy-minister-and-head-of-the-economic-and-social-council-launch-the-beirut-one-conference.html

This publication was produced as part of the XCEPT programme, a programme funded by UK International Development from the UK government. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies.